BLOOD SUGAR CAULDRON

by Tom Scanlan

I remember when War Heads sprang into existence because it’s when my problem started.

As a kid, I used to consume the hard sour candies until my tongue split and bled. The sugar (C6H12O6) became inseparable from my blood.

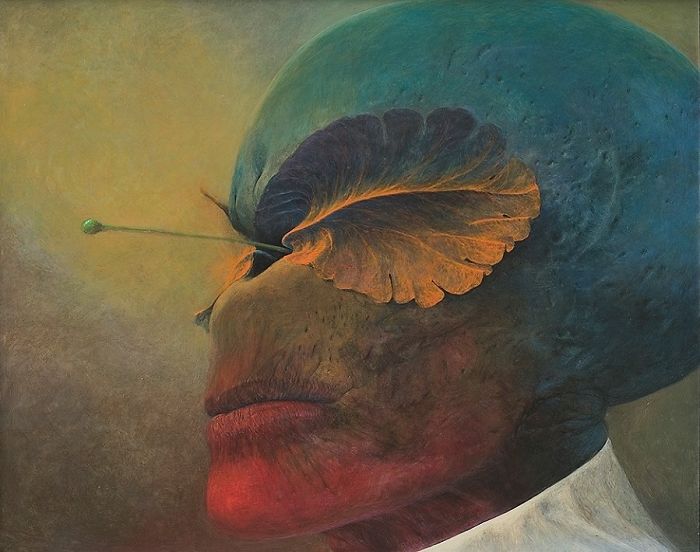

I changed.

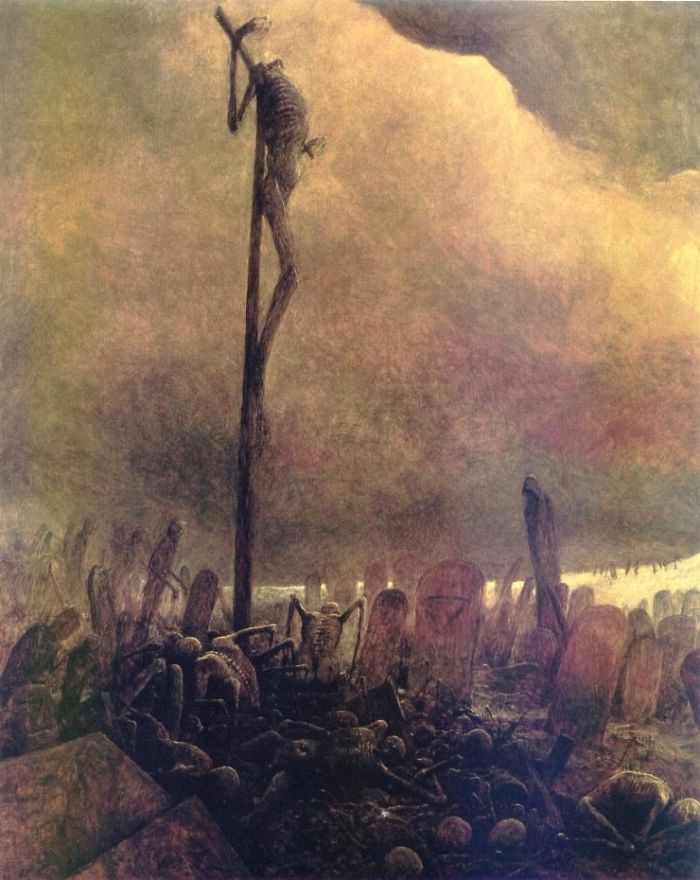

I yearn for Sour Patch Kids and the lesser sour candies still. I eat them until the roof of my mouth turns into dry whale ribs that I can run my tongue over, a xylophone that produces not sound but pain. I gorge myself on them at the expense of my body, which turns the sugar into fat that stuffs my skin like an overfilled sand bag.

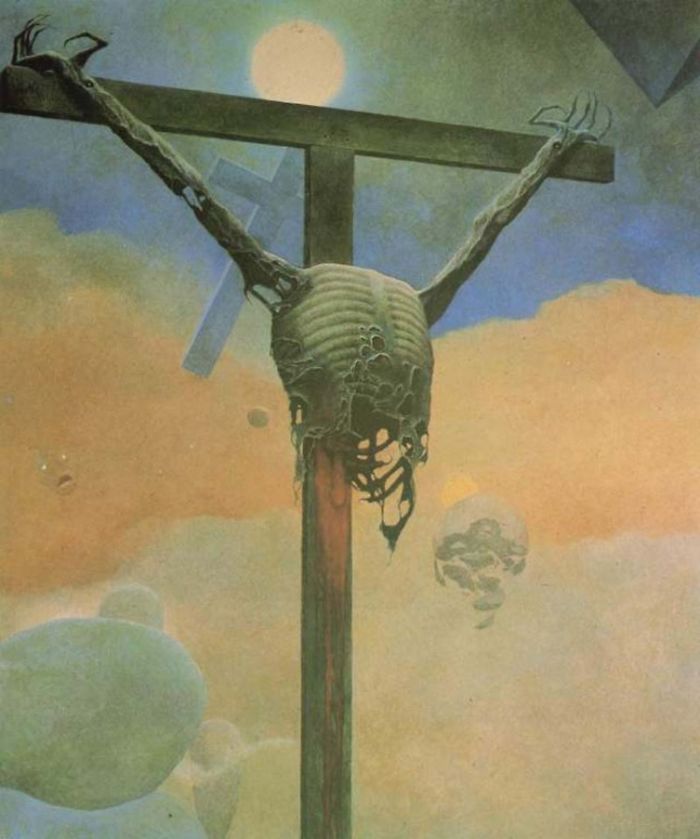

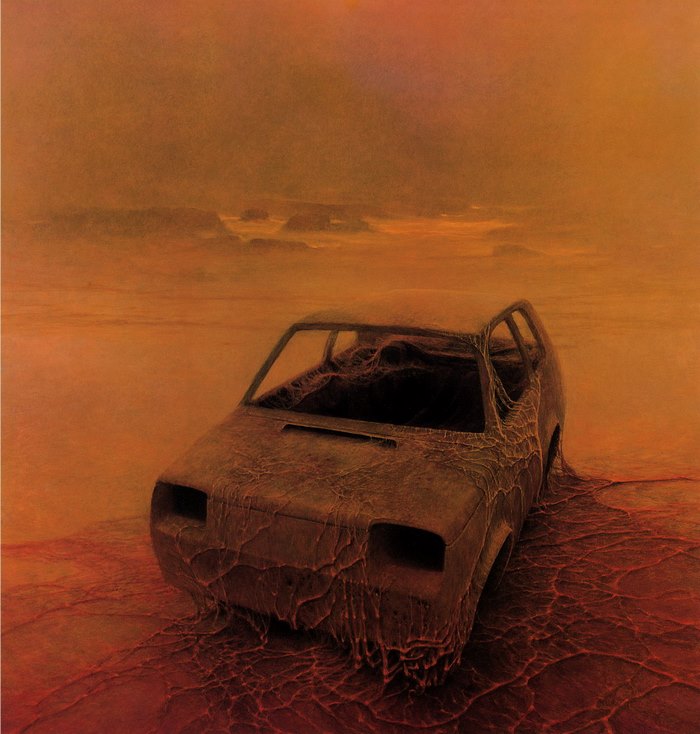

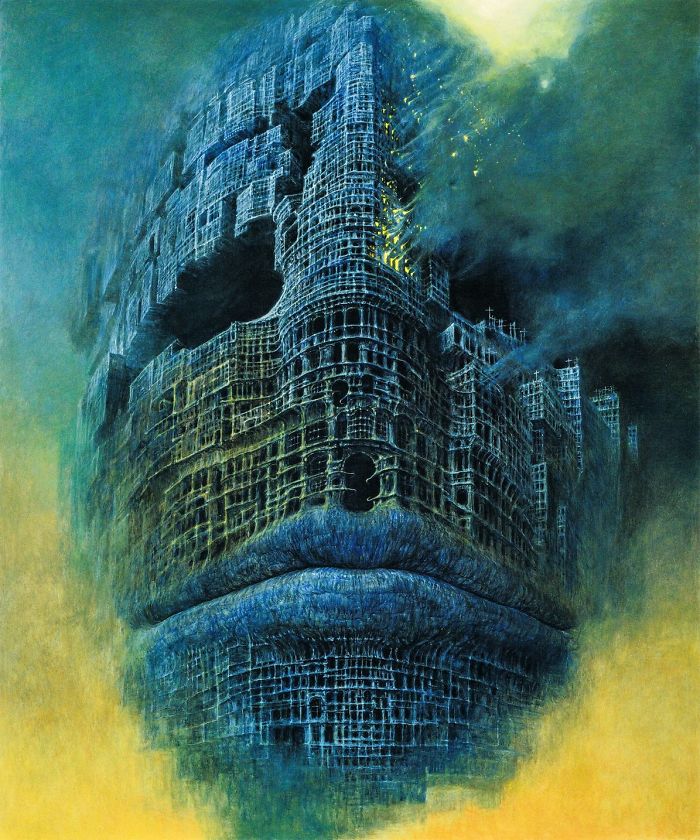

I’m in the 24-hour Seven Eleven. I come here while the world sleeps. I’m studying the candy section for my next selection, when I hear the universe chant unintelligible words. I see a vast cauldron nested in a corner of the cosmos. Dark amber glucose tar churns inside, popping, sizzling, letting off a sweet hot candy reek. The presence from whose mouth the chemical song comes ignores the spitting liquid scalding its space-time flesh.

Does the presence notice me notice it? I think it does.

I think it wants me to know.

Its ululations increase in volume. I need to blot out the noise. It sounds like something is being willed into existence…

Is the time now?

The bag of sour Now & Laters my glassy eyes have been looking beyond shakes. One by one, bags of Sour Worms, Sour Skittles, Air Head Xtreme Sours, Sour Jolly Ranchers, Sour Trollis, and the War Heads that started this journey, tremble. The plastic containers crinkle. The loose grains of sugar inside them shake like sand in maracas.

“YO.”

A pale employee with a neck beard looks at me intently.

“What?”

“I’ve been asking if you can hear me. Lay off the weed, dude. For fuck’s sake.”

“I’m not high,” I say. “I–” I can’t tell another person that I’ve been communicating with a deity I call (C6H12O6) about the progenation of its offspring.

I keep my mouth shut.

The cashier shrugs. “Fine. Whatever then. Stare at the candy until you get your heart’s fill.”

“Wait,” I say, before he walks away.

“Yup?”

I cough. My throat’s felt tight, but now I can breathe. “Bags. Please get me bags to carry my selection up. I’m going to need a lot of candy tonight.”

END

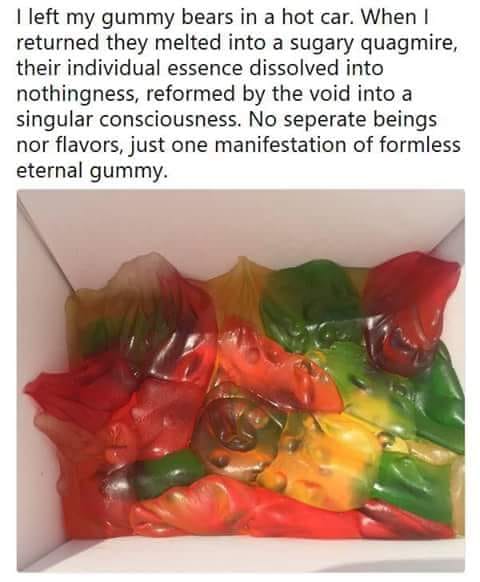

I started this post as a means of sharing this hilarious meme about gummy bears becoming a singular consciousness because they melted in a car. I thought I’d leave a funny line about how my die hard consumption of War Heads, as a 90s kid drawn to their “extreme sour” allure, contributed to candy somehow acquiring consciousness.

Then this flash piece took on a life of its own, and then a half-decent form, and then after a couple hours with it, I realized it’s kind of a cool story.

You know… “what if…

- you took a sweet (sour) tooth to its illogical extreme?”

- gave that creeper in the late-night convenient store setting a cosmic backstory?”

- considered that environmental forces and nutrition are already changing our bodies in ways no one could’ve foreseen in the 1950s, and gave that horror a dollop of glucose?”

Anyway, I don’t try flash fiction often. Let me know if this makes you think/feel anything!